Clint Eastwood Broke John Wayne's Biggest Western Rule

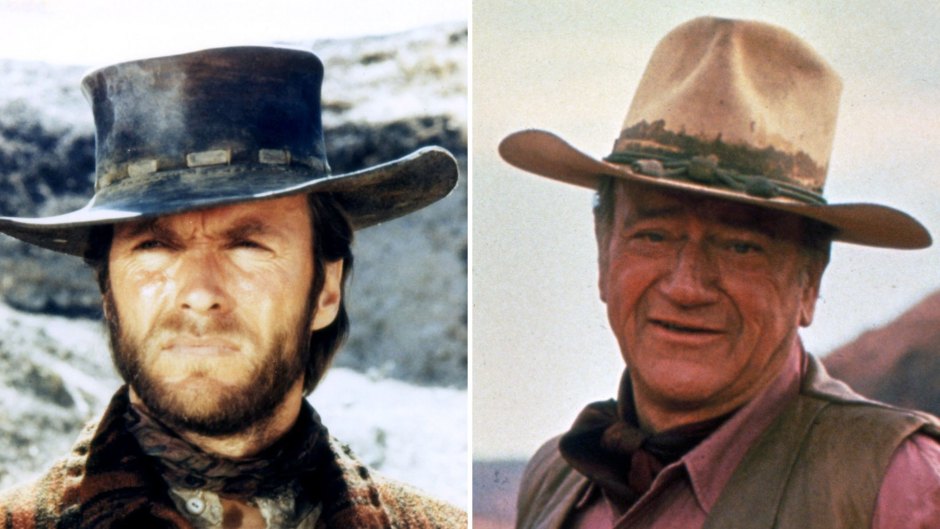

As the conspicuous essences of the Western kind and visionary portrayals of customary driving men, it's not difficult to contrast John Wayne and Clint Eastwood with one another. Playing chivalrous paradigms of ranchers, cops, and battle fighters, Wayne and Eastwood characterized a dream of American manliness for different ages. Their creative sensibilities put them in discussion with one another. In any case, the two celebrities contrasted in additional ways than one, particularly concerning their hesitance bringing out a flawless picture as legends. Wayne depicted noble Western sheriffs with a pleased feeling of respectability, while Eastwood's postmodern interpretation of the bandit introduced an uglier and evil underside of the Old West. The split between the two stars is exemplified by Wayne's refusal to shoot somebody behind the back, however Eastwood is in every case fast with the trigger, regardless of whether his foe soldier is surprised.

John Wayne and Clint Eastwood Played Very Different Western Heroes

An American symbol from the Old West to the Vietnam War, John Wayne was an amazing figure. His movies, remarkably with his productive colleague, John Passage, apparently addressed American culture and history. While Portage's most prominent accomplishments as chief, including The Searchers and The One Who Shot Freedom Valance, gracefully dismantled Western legends as manifestations of mythmaking, Wayne isolated craftsmanship from himself in his own life. Dissimilar to his peers, he decided not to serve in The Second Great War, and following this dubious choice, he embraced firm moderate standards. He helped out the Place of Unpatriotic Exercises (HUAC) during the 1950s to renounce claimed socialists working in Hollywood, and he rushed to name films as "unpatriotic." His entryway keeping of legitimate American qualities on the big screen advanced into unadulterated dogmatism, as proven by his notorious 1971 Playboy interview.

Clint Eastwood, starting with his breakout into the standard with Sergio Leone's Dollars set of three, conveyed the most desirable characteristics of Wayne's screen presence and developed his onscreen feelings. Wayne, whose sensational cleaves were in many cases excused, succeeded as an emotional entertainer when deprived of his gesture of being the quintessential All-American. In his jobs as Ethan Edwards in The Searchers and Thomas Dunson in Howard Falcons' Red Waterway, Wayne showed a more negative side to his chivalry, as these characters satisfied self centered wants including years of repressed dogmatism and capital additions, separately. With The Man With No Name, the nominal solitary officer in The Fugitive Josey Ridges, and William Munny in Unforgiven, Eastwood classified a person prime example tracked down across different classifications: the maverick criminal, an executioner with a smothered kind nature, and a clinical expert who talks meagerly. Westerns, right after Eastwood's progressive type deconstruction, Unforgiven, were supposed to follow wannabes with tormented spirits.

"At the point when you need to shoot, shoot, don't talk!" This clever Western rationale presented by Tuco (Eli Wallach) in Leone's The General mishmash filled in as the spine to Eastwood's Western characters. He rarely talked and discharged his firearm on intuition. Examiner Harry Callahan of the Messy Harry series embraced a vigilante way to deal with fair treatment: shoot first and pose inquiries later. The speedy trigger of these characters saw no limits, even inside the unwritten guidelines of the Western classification. Besides the fact that Eastwood's criminals shot individuals accidentally, he couldn't have cared less assuming his adversary was taking out their weapon. Because of their unfavorable names, (for example, the anonymous "Minister" in Pale Rider) and restricted measure of discourse, Eastwood conveyed a mysterious screen presence. His scheming ways cast a dull shadow on characters celebrated as respectable vigilantes. In Eastwood's haziest movies, including High Fields Vagabond, his cattle rustlers encapsulate a sinister soul reviled on society, and genuine malicious surprises you while unguarded.

Unlike John Wayne, Clint Eastwood Would Shoot People Behind Their Back

The unmistakable difference between John Wayne and Clint Eastwood is exemplified by a story spoken by Eastwood as a visitor on Inside the Entertainer's Studio. Have James Lipton noticed that Leone's Dollars set of three broke the highly contrasting/good clashing with detestable shows of the Western type, obvious by Eastwood's anonymous criminal declining to trust that his foe warrior will take out their weapon prior to shooting. While portraying the reasoning behind shooting first, Eastwood wryly inquired, "It doesn't check out, how could you sit tight for someone?" which drew a major chuckle from the Entertainer's Studio crowd. Regardless of being the substance of the cutting edge Western, Eastwood dissects the class like a professional comedian playing out a routine ridiculing its strange parts.

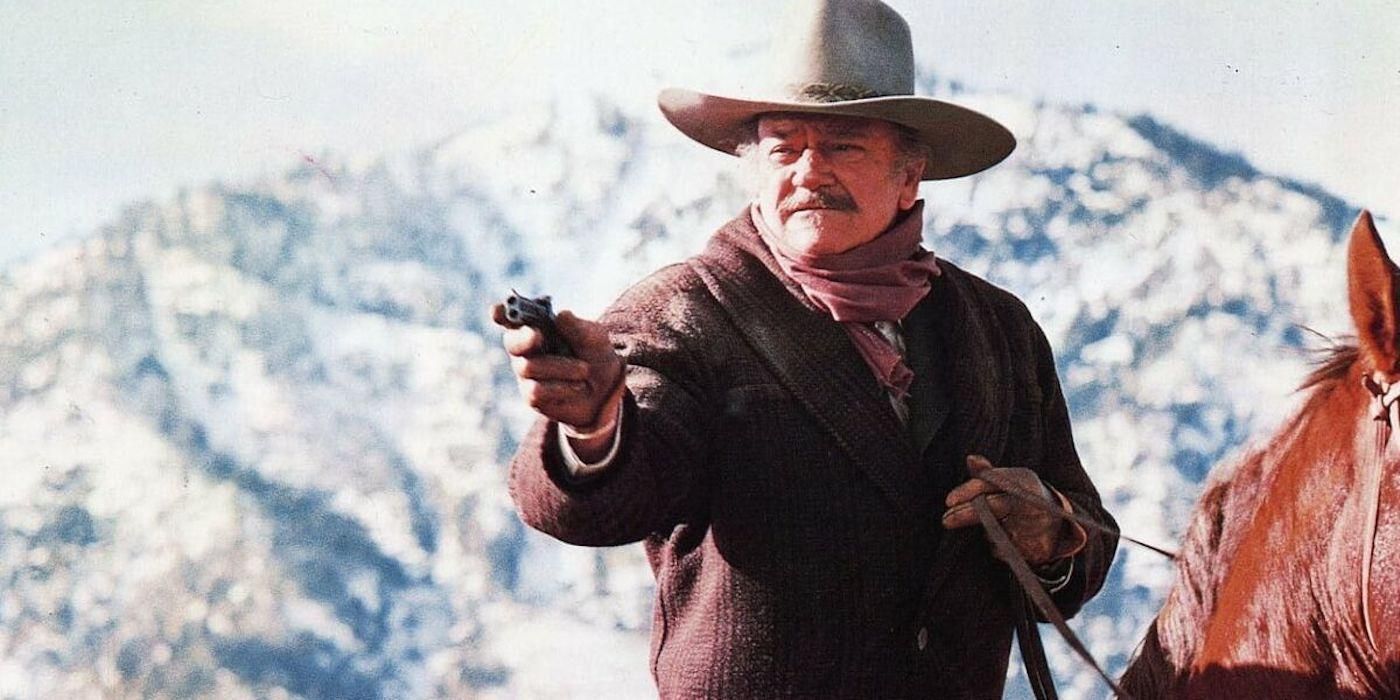

Eastwood then, at that point, reviewed a story he heard from Wear Siegel, overseer of Messy Harry and a modest bunch of Eastwood films, who likewise filled in as a coach for the entertainer's introduction to coordinating. In 1976, Siegel coordinated John Wayne in The Shootist, The Duke's last film, which tracks a withering gun slinger as Wayne's wellbeing was disintegrating, all things considered. While recording a scene where Wayne creeps up behind a foe gun slinger, Siegel advised him to shoot him. "'Well, I shoot him toward the back?'" Eastwood reviewed Wayne's remarks. "'I don't shoot anybody toward the back,'" Wayne told Siegel. The chief, as Eastwood put it, "made a horrible blunder," by illuminating his star that Eastwood would have shot this individual toward the back. Obviously, Wayne, a man of hypocritical pride, was irate over this remark. Eastwood, talking in a wide impression of Wayne, said, "'it doesn't really matter to me what that youngster would have done. I won't shoot him toward the back!'"

The Drastic Differences Between John Wayne and Clint Eastwood Sparked a Feud

In spite of their actual similitudes, tall height, serious look, and forcing non-verbal communication, Wayne and Eastwood's imaginative sensibilities varied. It's not only that Wayne contradicted Eastwood's translation of the American outskirts, he found his perspective an attack against his country. During the '70s, the two film cattle rustlers participated in their very own duel after Wayne turned down an opportunity to work with Eastwood. Passionately went against to Eastwood's vision, the Duke sent him a scorching letter evaluating High Fields Vagabond. Eastwood refered to the film, about a brutal gun slinger employed to safeguard a town in danger, as a preventative tale, yet Wayne denounced it as a treacherous text. Maybe the film hit excessively up close and personal for Wayne, as Eastwood's anonymous bandit unflinchingly introduced Western fantasy as a revile on society. All in the film, the limits between a respectable vigilante and a heartless savage are broken, as Eastwood's personality serves equity through viciousness, however the town loses its ethical quality. Wayne, who fabricated his vocation off maintaining enthusiastic qualities in the Western classification, could plausibly perceive the sobering reality that his jobs addressed.

Western bandits and gun slingers are intended to kill past the boundaries of the law. One way or another, whether they do it to their face or despite their good faith, murder is their reason for living card. While John Wayne picked to disinfect the portrayal of cattle rustlers, Clint Eastwood introduced the crude reality of American old stories. His skill for depicting liberated dimness in his characters made him a definitive revisionist chief — honoring Wayne's iconography while developing his directives for the cutting edge period.